Dr John Chipman

Esteemed Co-Panellists

Pak Ryamizard

Minister Ron Mark

Introduction

First on behalf of my colleagues at the Ministry of Defence (MINDEF), Senior Minister of State Heng Chee How, Senior Minister of State Maliki and Senior Minister Teo, thank you all for being here this Shangri-La Dialogue (SLD). We are very thankful, especially for our Muslim colleagues, because this is a month of Ramadan and I seek your understanding that these meetings are booked ahead of time at a fixed slot within the year and sometimes it coincides and I ask for your understanding for the discomfort it might have caused you. I want to thank especially all of you for being here and for contributing to the various discussions. If there is any reason why the SLD is relevant, and some would say impactful, it is because of your presence and I want to thank you for taking time to be here.

Over the past 18 years, since the inception of the SLD in 2002, we have had the privilege to observe history in the making for this region; some here even as principal actors. Since then, at each SLD – dubbed Asia's premier Security Summit – we have dissected, commented, criticised, argued and sought consensus on the way forward toward a stable, progressive and inclusive region, primarily for security, but just as important, for economic prosperity, because security and economic progress are but two faces of the same coin.

US-China: Tracing History to the Present

By historical timelines, 18 years is but a blip and yet much has occurred for those of us who lived through these times. It is not an exaggeration to state that through the last two decades, Asia has been transformed. But events in the last month or so, specifically the breakdown of a trade deal between the United States (US) and China, and in its place, the tariff and technology barriers erected between them, have altered the trajectory of this region onto an altogether different orbit. Year after year, many at the SLD had cautioned against this outright rivalry between the two leading economies and militaries of the world. Even so, it has come to pass, with potential for great harm on all countries here and beyond. How did we get here?

When SLD was first launched in 2002, a decade or so had passed since the US and its Western Allies had won the Cold War. There was a mood to reap the peace dividend. A published report by the National Intelligence Council on Russia in 2001, predicted that Russian foreign policy moving forward would be characterised by "weakness and frustration, primarily with the US as the pre-eminent power, over Russia's weakness". One must remember that since 1991 then, Russian working age males had a 60% increase in mortality: in deaths from alcohol abuse, traffic accidents and violent crimes. It was, in medical parlance, a social phenomenon and something which we rarely see.

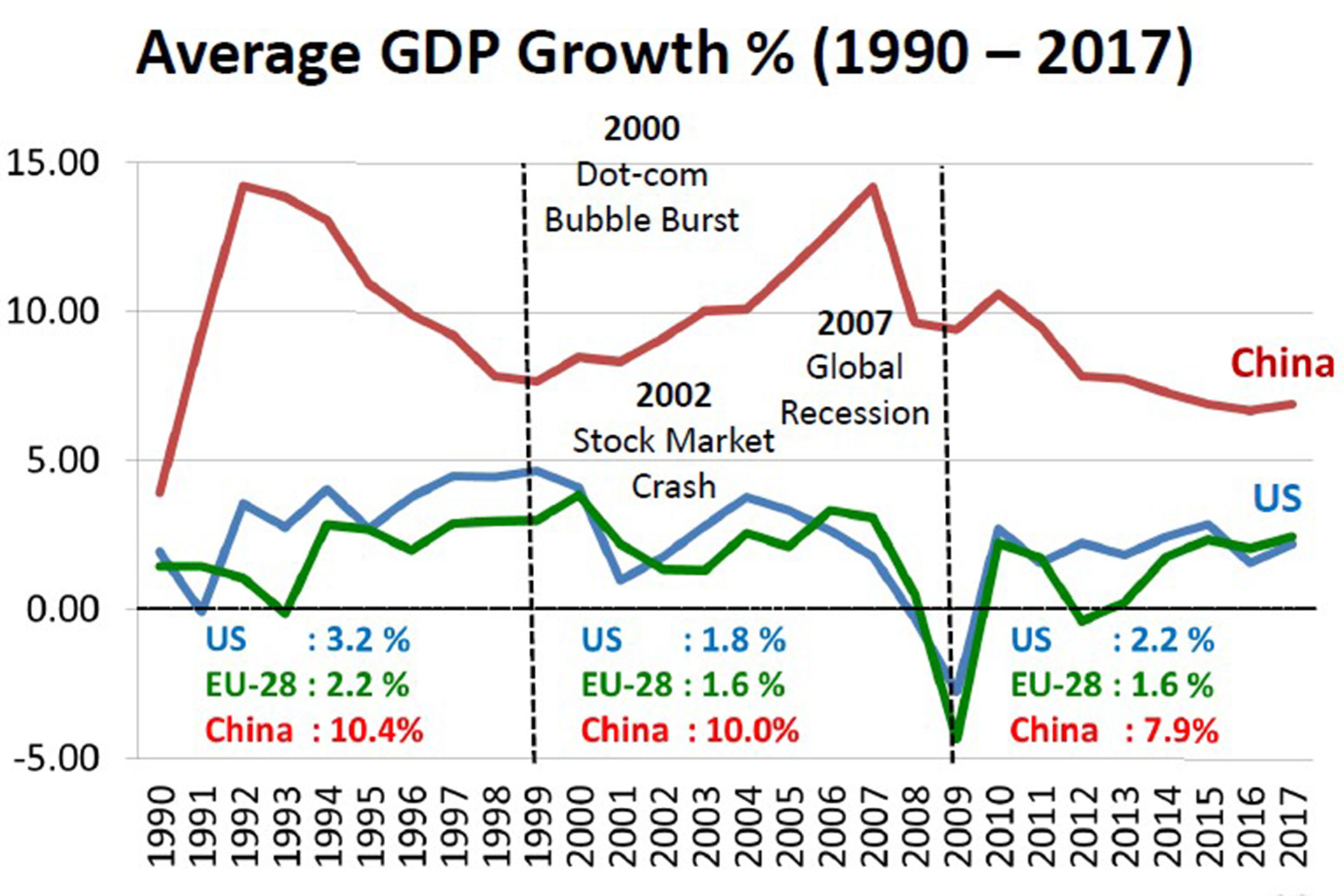

Even so, economic prosperity was not one of the direct "peace dividends" to be reaped by the US or Europe. Instead, the average annual GDP growth of the US fell by almost half – from 3.2% in the 1990s to 1.8% from the 2000 to 2009, as a result of three economic setbacks – the dot-com bust in 2000, the stock market crash of 2002 and the global recession of 2007. Since 2010, the US economy has grown slightly faster – but only at an average of 2.2%. Europe too experienced average annual GDP growth at 1.6% throughout the 2000s [Figure 1].

Neither was prolonged peace for the US and its allies achieved after the Cold War. Following the 9/11 attacks, their military deployments in the Middle East have been the longest since WWII. The war on terror continues, as we speak, with a hefty bill, now estimated to have cost the US $1.5 trillion since 2001.

If the US and its Western liberal democracies expected to bask in the Golden Age of Capitalism, post-Cold War, it certainly did not fully materialise.

In contrast, it was China – after Deng Xiao Ping lifted the Bamboo Curtain to focus on economic growth – that flourished as a dazzling debutante in the globalised ball, and with it much of Asia. In contrast to the US' and Europe's sub-2% growth, China recorded an astonishing average annual GDP growth of 9% over 2000 to 2017. [Figure 1] China accounted for 13% of global trade in 2017, more than a three-fold rise from 4% in the year 2000. The US' and EU’s share declined – the US' share declined from 12% to 9% and the EU’s from 39% to 33%. As could be anticipated, China has been the main trading partner of ASEAN countries since 2009, and replaced the US as the world’s largest trading nation in 2013.

It was with this ascendant China that President Xi Jinping took office in 2013, and pushed for China to play a larger role in global affairs. Xi set a national agenda to achieve the two milestones of centennials of the founding of China in 2049 and the CCP in 2021. Military spending from China increased pari passu with economic growth – Chinese defence expenditure increased exponentially from US$41 billion in the year 2000 to US$204 billion in 2015. China also became more assertive in its position in the South China Sea, now defined as a core interest. In the economic sphere, the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) was launched in 2013. Today, at least US$700 billion has been committed for the BRI, seven times that of the Marshall Plan, with the potential to become the most impactful macroeconomic undertaking in our world for this century.

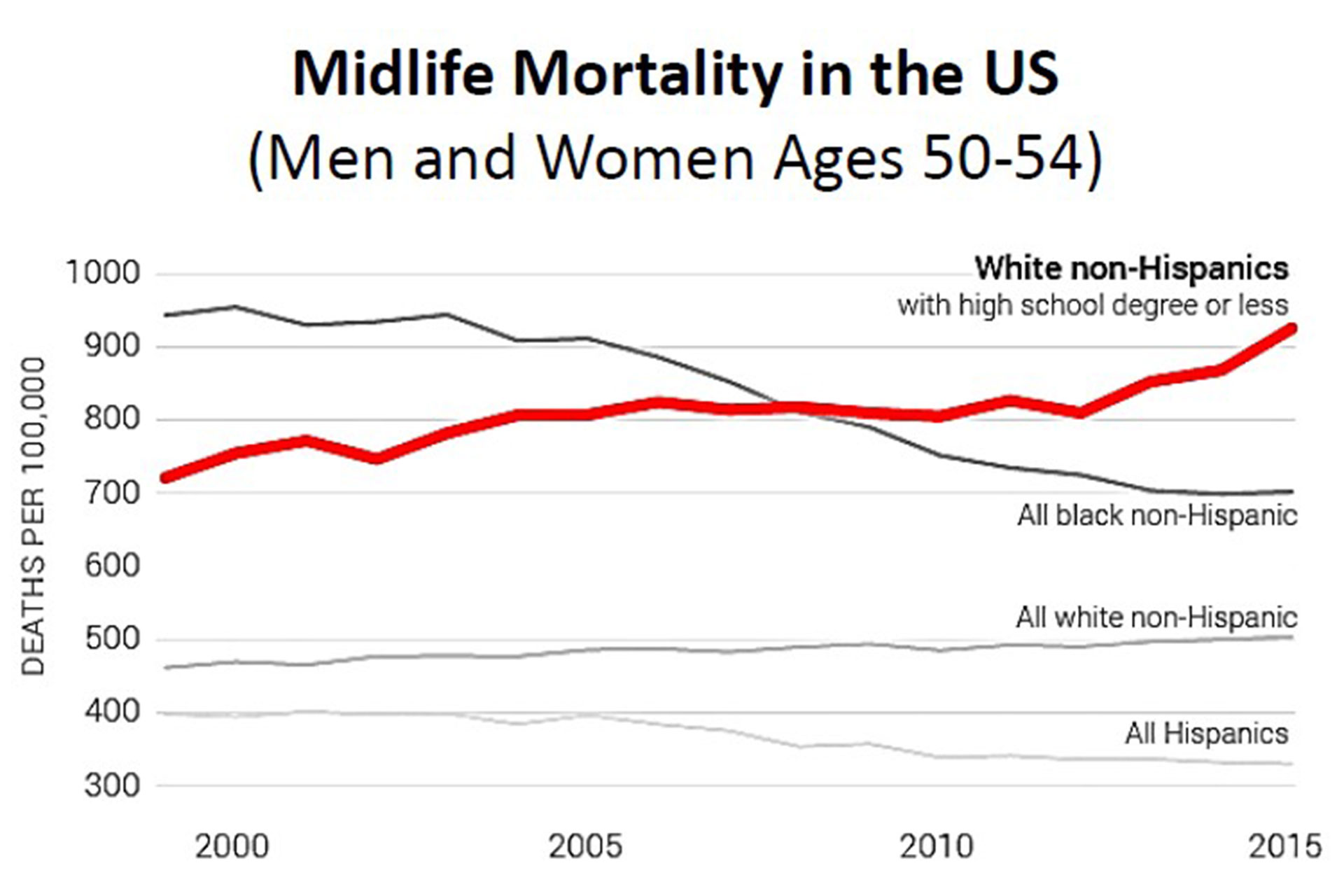

Perhaps and in retrospect, this state of paradoxical fortunes of victors and those supposedly vanquished was never sustainable. When I read the reports by Princeton researchers in 2017, that documented a sharp decline in the life expectancy of middle-aged working class white Americans from "deaths of despair" due to alcohol abuse, suicides or drug overdose, it was a micro-data point that explained much of why US domestic politics had changed. [Figure 2] Those rising death rates were nearly two-fold compared to minorities. In other words, working-class middle-aged Americans had a two-fold death rate compared to minorities in the US as well. Especially in the Rust Belt, and this explained in some part the success of the Trump campaign and subsequent victory in the Presidential election. There was a déjà vu with the Russian males’ experience post-Cold War – a rise in mortality. Vastly different contexts, but in both instances, the angst and vitriol of citizens whose lives had worsened clamored for strong man politics to right perceived wrongs.

The new trajectory is now that of a US foreign policy to redress the perceived imbalances accumulated over the past two decades – encapsulated in America First, and according to this narrative, an America that has been taken advantage of. We can understand, even appreciate the underlying motivations but the implications are as troubling as they are unpredictable. It is, in essence, a disruptive change, not only for the US and its allies, but indeed the world. The crystal ball, if it was ever clear, is now densely fogged. Questions abound.

On trade, how far, wide and long will the US pursue this tack of tariff and technological barriers? How will those US efforts, if persistent, impact the current global trading system? Will the result be mere additions and alterations or much worse, denouement of the last 70 years of the efforts for globalisation? Can the multilateral trading systems even survive, especially when it clashes against US-led trading blocs and China-dependent economies?

One aspect is clear – few think the world will grow at a faster pace in the near future, with such uncertainty hanging over us all. With slower growth, how will China be impacted, whose workforce is expected to decline by 200 million by 2050, with social spending for an ageing population set to increase? What pressures might China, in responding, put on other countries that are economically dependent on it? More importantly, how will the Communist Party of China shore up its political legitimacy, if their economy slows? For the US, how does this shift to a new, more transactional foreign and security policy affect their acceptance by other nation states, friends, even allies?

Looking Towards the Future

The challenge for both the US and China, amid their bilateral struggle, as dominant powers in Asia, is to offer that inclusive and over-arching moral justification for acceptance by all countries, big and small, of their dominance beyond military might. Both countries have cited security as the basis for their current positions – the US in trade, and China in the SCS. But whatever the underlying motivations, for either country, if America First or China's rise is perceived to be lopsided against the national interests of other countries or the collective good, the acceptance of US' or China's dominance will be diminished. Countries will hedge: first in trade ties, and later inevitably in security alliances. We saw this in the Trans-Pacific Partnership or TPP, where eleven nations chose to proceed after the US pulled out, with the Japanese and Australians leading to establish the eleven-member CP-TPP. Even China has not said no to joining the CP-TPP. For the EU, if it perceives that the US' terms for trade are too onerous to bear, it is not inconceivable that it might even increase its engagement with China or seek other partners, apart from the US. Worse still, is the situation where individual countries have to choose between the US or China. Be it in technology, be it in trade, security or comprehensive partnerships. That will be the ultimate losers' game and a race to diminishing benefits for all concerned.

Conclusion

What is at stake is the existing global order, that even if not perfect, has ensured peace and progress these past 70 years. It would be an egregious folly to throw this baby out with the bath water.

It remains for me to thank all of you for your presence and contributions at SLD. Let me put on record our deep thanks to Dr John Chipman as chief Sherpa, with your other Sherpas as you guide us to ascend the summits of detente, if not partnerships. I also want to put on record, and I am sure all of you would agree, our thanks to our Police, our Civil Defence Force, and our MINDEF officers, and SAF officers who have facilitated your visit, your calls and made this event of value to you. Thank you very much, I wish you all safe journeys and goodbye.

Figure 1: Average GDP Growth (%) from 1990 to 2017

Figure 1: Average GDP Growth (%) from 1990 to 2017

Figure 2: Midlife Mortality in the US (Men and Women Ages 50 – 54) [Source: Case and Deaton, 2017]

Figure 2: Midlife Mortality in the US (Men and Women Ages 50 – 54) [Source: Case and Deaton, 2017]